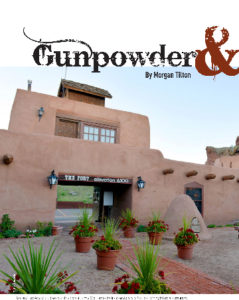

The menu options at The Fort Restaurant in Morrison harken back to the restaurant’s inspiration—19th century Bent’s Old Fort near La Junta. Bonds between the two destinations grow stronger with each new (historic) recipe.

*Bronze prize: North American Travel Journalists Association, Print Historical Travel category

EnCompass Magazine | March 2015

By Morgan Tilton

Click here to read the story on the EnCompass website

The acrid smells of a rifleman’s gunpowder and a trail cook’s roasted green chili stick to the hot breeze. The clang-clang of a blacksmith’s hammer melds with billows of smoke that lift off toward the west. Beside the blacksmith, a tanner tugs a mule-deer hide taut across wooden poles. I hear someone call out in the distance, “Taffy! Molasses taffy!”

Mingling with couples and families, the sounds and smells slingshot me 180 years back to the old Santa Fe Trail—about 189 miles southeast from where I stand. I’m strolling through the 1830s Rendezvous and Spanish Colonial Art Market, an annual September event established by The Fort Restaurant outside Morrison. Nestled in red rocks country, with alluring front-row views of Mt. Falcon to the west and Denver’s urban-stretching glimmer to the east, The Fort Restaurant is modeled after an old yet still-significant fortress in Colorado’s southeastern plains, eight miles from La Junta and along the Arkansas River. That long-ago trading post, Bent’s Old Fort, inspired not just the Morrison restaurant’s architecture, but also its “Paleo” menu, and for a time, its resident bear.

FLOWING CULTURE ALONG THE ARKANSAS

In the 1830s and 1840s, covered wagons rolled commerce across the country along the Santa Fe Trail. The byway paralleled 900 miles of riverways from Missouri to then-Mexico’s town, Santa Fe. The trail’s western portion provided an alternate northern “mountain route,” which followed the Arkansas River to Bent’s Old Fort. Adventurers and journalists stepped inside the citadel’s walled courtyard to observe and record the intermingling of cultures and languages—English, Spanish, French, and various tribal languages. Traders delivered coffee, spices from India, and Chinese silks, which had been transported overseas from London and Paris. Caravans from Chesapeake Bay toted fresh oysters, packed in large oak casks between layers of shaved ice and cornmeal. The creatures would plump up during the three-month journey. Trappers carried beaver, caught in the Rockies. Plains Indians brought handmade buffalo robes, and hunters supplied buffalo meat. Mexicans wrestled oxen, and peacocks stood guard. The fort’s council room hosted peace talks and intertribal meetings.

It was the interfusion of culture at the old fort that came to inspire the founders of The Fort Restaurant in Morrison.

Before The Fort became a restaurant, it was initially the adobe dream home of Sam and Bay Arnold. They based the home’s design on an 1845 sketch of the original Bent’s Old Fort, drawn by James Abert. Lovers and preservers of history, Sam and Bay set out to replicate the building as authentically as possible. At the time, the national site’s reconstruction hadn’t begun—and wouldn’t be completed until 1976—so the couple hired top architect William Lumpkins to help them develop blueprints, based off the Colorado Historical Society’s excavation of the fort’s primitive ruins. The Fort became the first-ever re-creation of Bent’s Old Fort. During construction, 22 laborers hand-built 80,000 bricks from soil. An oxen blood floor was poured, and the couple ordered hand-carved furniture and doors. When costs got out of hand, a bank office suggested, “Why don’t you open a restaurant?” So they did.

PRAIRIE BUTTER, ‘PALEO’ DIET, AND THE PIONEERS

Sam and Bay developed the menu, and—just like their adobe home—the past was their impetus: They unearthed the diaries and recipes of the old pioneers. The couple learned the time period’s staples and delicacies, such as “prairie butter”—which is buffalo bone marrow—written about by trader wife Susan Magoffin. With time, Sam’s resource collection grew to include more than 3,000 rare cookbooks and Western historical documents. Holly, the Arnold’s daughter and The Fort’s present-day proprietress, is still cataloging the extraordinary library today, which stands reserved in cherry wood bookshelves in her Denver home.

“My parents both loved food history and held on to cookbooks from their families,” Holly shares with me as we sit outside on The Fort’s back stone patio one cool summer evening, warmed by the mellow breeze. “They had an interest and passion for preserving culture through food. So, they said, ‘Let’s serve the foods of what would’ve been eaten at the original Bent’s Old Fort.’”

The Fort’s menu includes elk, quail, rabbit, and buffalo—primary proteins of Native Indians pre-colonization and the French mountain men who visited Bent’s Old Fort. The trading post also served East Indian curry and Mexican posole. Furthermore, Bent’s Old Fort became infamous for bootlegging. Traders watered down booze to extend their profitability and invented surefire cocktails with strange, flavorful ingredients. One such libation was “trader’s whiskey”—which Holly discovered in early trappers’ journals and found to be surprisingly tasty: old-fashioned black gunpowder, dried red peppers, bourbon, and tobacco. Once Holly began studying the Paleo diet, she realized how similar it is to the restaurant’s old-age style menu.

“It’s a pretty restrictive diet that excludes sugar, dairy, wheat, and salt,” Holly said, closely matching the food eaten at Bent’s Old Fort. “We can cook a steak with a dry red chili rub—our ‘Paleo rub’—and smother bone marrow on top, like butter. Bone marrow is an unsaturated fat and incomplete protein, and is very good for your immune system—it’s what makes red blood cells for animals. Bone marrow is perfect for Paleo: It makes up for not having salt.”

Enthusiastic about the correlation, Holly reached out to Paleo movement founder Loren Cordain. A former Colorado State University professor, Cordain first encountered the nutritional concept in 1987, when he read “Paleolithic Nutrition,” an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, by S. Boyd Eaton, M.D., and Melvin Konner, Ph.D., on Jan. 31, 1985. In April 2014, the duo hosted a “Paleo” dinner at The Fort with a lecture led by Cordain. Dessert included, the night was a hit.

MODERN MEETING PLACE

Adorned in an ivory blouse and turquoise necklace, Holly strolls lightly from the porch toward our table inside the restaurant’s veranda-style wing. Pleasantly unhurried, she’s seemingly unaffected by the pace of urban life. To start, she orders us the wild portabella and shitake Forest Mushrooms plate, and President Jefferson’s favorite Mac ‘N’ Cheese—a savory macaroni and cheese pudding, which, to my surprise, was a documented meal at Bent’s Old Fort. She persuades me to try The Fort’s Game Plate—elk chop, buffalo sirloin, and quail topped with Montana huckleberry preserves.

As we dine, Holly tells me that the restaurant, like its inspiration, is intended to stand at the crossroads of culture. It’s a living history museum, but is also a modern-day meeting ground, where the heirs of Kit Carson, Owl Woman, and William Bent have gathered around the table. The Fort preserves the past and revives the Old Fort’s glory: It is here that the world’s traditions and culture continue to meet—and share delicious prairie butter.

SELECT RECIPES FROM THE FORT

BOWL OF THE WIFE OF KIT CARSON (CALDO TLALPEÑO)

Serves 4 to 6

Holly and her family first tried this dish while road tripping in Mexico in 1961. What’s the dish’s secret? The chipotle chili—which is smoke-dried jalapeño—and its blended flavor of smokiness and spice. Now a Fort bestseller, the Arnolds renamed the soup after Leona Wood (who ran the gift shop/trade room in the restaurant’s early days) confirmed that her grandmother had made it for her: Leona was the last granddaughter of frontiersman Kit Carson, who frequented Bent’s Fort.

2 whole boneless, skinless chicken breasts (close to 2 pounds)

4 to 6 cups chicken broth

1/4 teaspoon dried Mexican leaf oregano, crumbled

1 cup cooked, dried garbanzo beans (chick peas), or canned garbanzos, rinsed and well drained

1 cup cooked rice

1 chipotle chili (canned), packed in adobo, minced

4 to 6 ounces Monterey Jack or Havarti cheese, diced

Garnishing

Avocado

Cilantro

1 fresh lime, cut into 4 to 6 wedges

In a large saucepan, heat the chicken breasts and broth over medium-high heat. Scrape off any foam that rises. Once boiling, turn off the heat, cover, and let the chicken poach for 12 minutes. Then, remove and slice the chicken into 1 1/2 inch long strips. Return the chicken to the broth. Add the oregano, rice, garbanzos, and chipotle, and bring the soup to a boil. Divvy the cheese equally among the soup bowls, then ladle out the soup.

PUMPKIN-WALNUT MUFFINS

Makes 3 dozen mini muffins or 12 to 16 large muffins

American Indian diet included various squashes (counting pumpkin), and when early 1800s fur trappers arrived, pumpkin became a central part of their diet, too. At Bent’s Fort, Rufus Sage, a mountain man and journalist, wrote about a group of Taos Mexicans who arrived with a sweep of items to barter, including dried pumpkin.

1 1/3 cups all purpose flour (1 cup + 3 tablespoons at sea level)

1/2 cup brown sugar (1/2 cup + 2 tablespoons at sea level)

1/3 cup granulated sugar (1/3 cup + 2 tablespoons at sea level)

1 tablespoon baking powder (1 tablespoon + 3/4 teaspoon at sea level)

1 1/2 teaspoons ground cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup chopped lightly toasted walnuts

1/2 cup golden raisins

1 large egg

1/3 cup plus 1 tablespoon canola oil

1/3 cup plus 1 tablespoon 2% milk (1/3 cup at sea level)

1 can (15-ounces) pumpkin (not pie filling)

Preheat the oven to 350° F. Grease 2 mini muffin tins or 1 large muffin tin, or line with paper baking cups. In a large bowl: Combine flour, sugars, baking powder, cinnamon, and salt. Stir in walnuts and raisins. In a separate bowl: Whisk the egg, canola oil, milk, and pumpkin. Then, gradually stir the pumpkin mixture into the dry ingredients. (The batter should be easy to scoop. If not, add a little more milk.) Fill each muffin tin three-quarters full. Bake mini muffins 25 to 30 minutes (45 to 50 for larger muffins) or until a toothpick inserted in the center of a muffin comes out clean. Rotate muffin tins once halfway through baking to ensure even baking. Let muffins cool for 10 minutes before removing them from the tins.

WASHTUNKALA CAST-IRON KETTLE STEW

Serves 4 to 6

American Indians utilized every part of a killed buffalo, which still vastly roamed the plains in the early 1830s. A portion of the meat was sliced and hung to dry, and saved for winter recipes, including washtunkala: a Sioux word meaning stew made with dried meat and cornmeal. They’d mix in dried maize and squash, cattails, wild onions, garlic, and prairie potatoes.

1 1/2 to 2 pounds buffalo cut into 1 1/2-inch cubes

3 to 4 tablespoons olive oil

Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

1/4 cup fresh thyme sprigs

One 12-ounce package frozen pearl onions

One 12-ounce package frozen corn

1 1/2 chopped mild green chilies (one 7-ounce can, plus one 4-ounce can)

4 cups rich buffalo stock

1/2 cup roasted sunflower seed hearts (hulled seeds)

Optional: You can replace the buffalo with beef tenderloin tips and the buffalo stock with beef broth.

Use dry paper towels to soak extra moisture off the buffalo cubes. In a large pan, sauté the meat in oil, over high heat, until browned. (Make sure the pan isn’t too crowded.) Then, salt and pepper the meat, and add the thyme, onions, corn, and chilies. Sauté for 1 minute, then pour in the buffalo stock and sunflower seeds. Reduce the heat and simmer for 8 to 10 minutes at low, until the broth thickens a tad.

For more recipes, purchase Shinin’ Times at The Fort, at the restaurant or online